En Español | Reddit Thread | Hacker News Thread

Microservices became a very popular topic over the last couple of years1. ‘Microservice madness’ goes something like this:

Netflix are great at devops. Netflix do microservices. Therefore: If I do microservices, I am great at devops.

There are many cases where great efforts have been made to adopt microservice patterns without necessarily understanding how the costs and benefits will apply to the specifics of the problem at hand.

I’m going to describe in detail what microservices are, why the pattern is so appealing, and also some of the key challenges that they present.

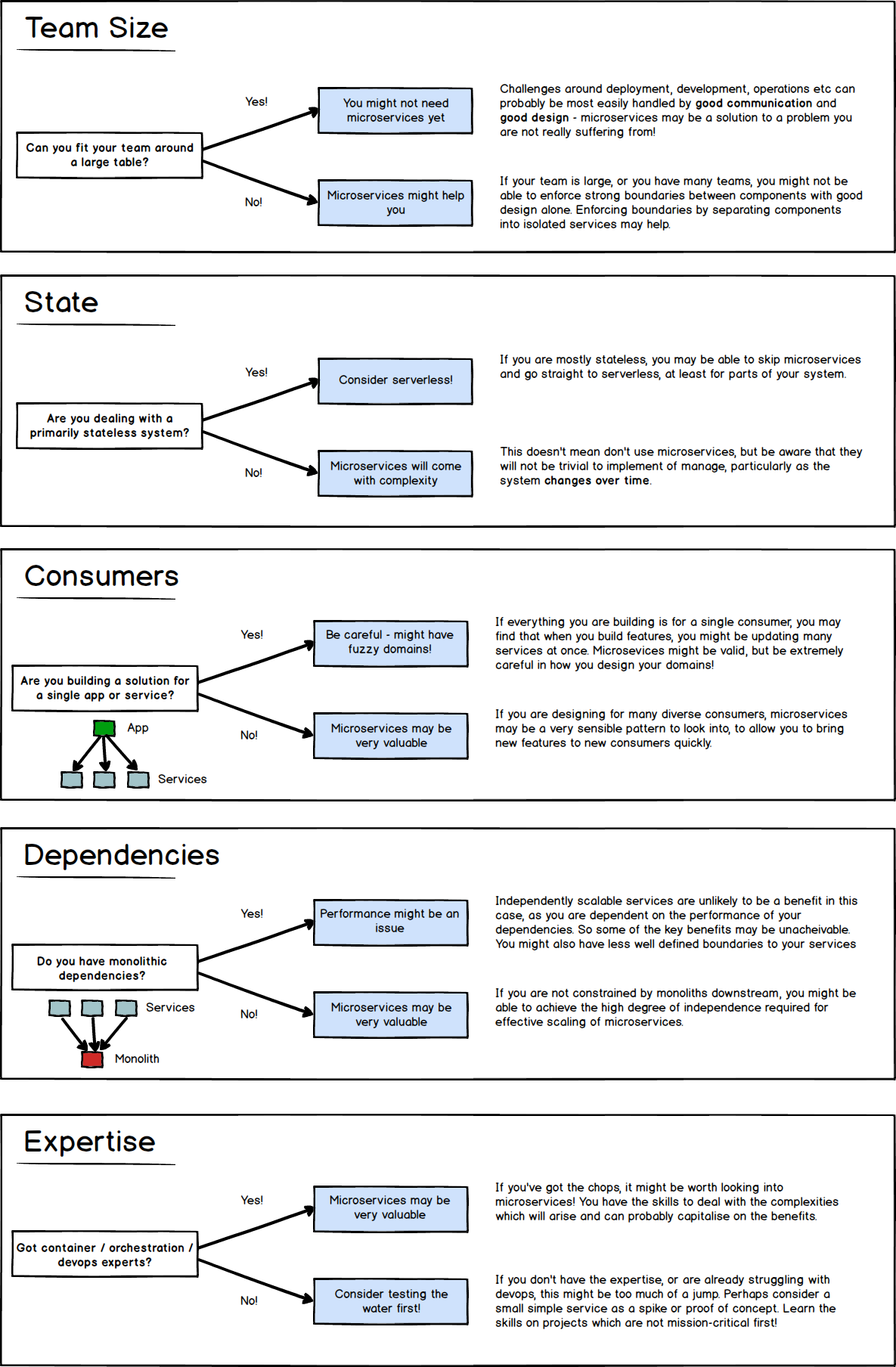

I’ll finish with a set of simple questions might be valuable to ask yourself when you are considering whether microservices are the right pattern for you. The questions are at the end of the article.

What are microservices, and why are they so popular?

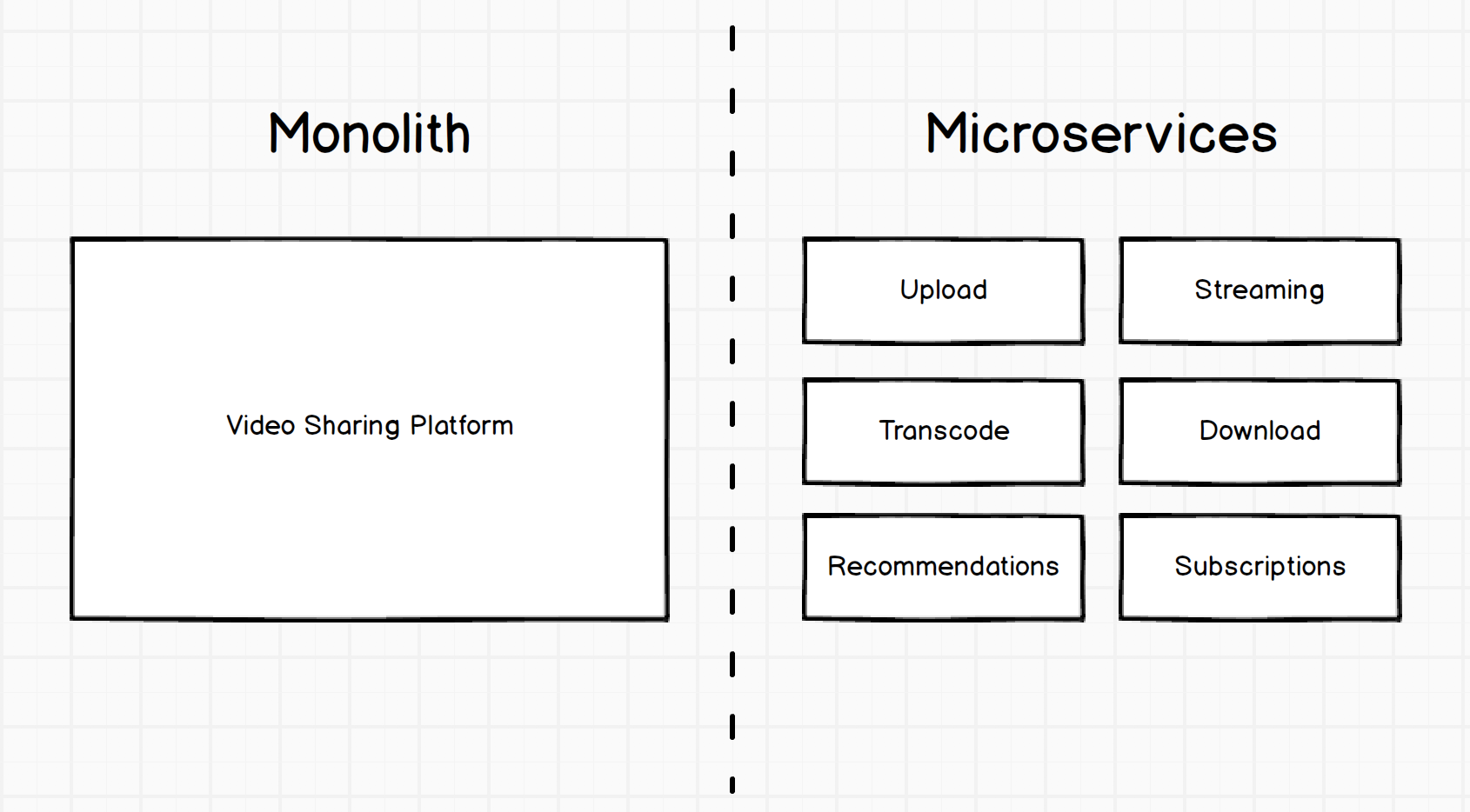

Let’s start with the basics. Here is how a hypothetical video sharing platform might be implemented, first in the form of a monolith (single large unit) and then in the form of microservices:

The difference between the two systems is that the first is a single large unit; a monolith. The second is a set of small, specific services. Each service has a specific role.

When the diagram is drawn at this level of detail, it is easy to see the appeal. There are a whole host of potential benefits:

Independent Development: Small, independent components can be built by small, independent teams. A group can work on a change to the ‘Upload’ service without interfering with the ‘Transcode’ service, or even knowing about it. The amount of time to learn about a component is greatly reduced, and it is easier to develop new features.

Independent Deployment: Each individual component can be deployed independently. This allows new features to be released with greater velocity and less risk. Fixes or features for the ‘Streaming’ component can be deployed without requiring other components to be deployed.

Independent Scalability: Each component can be scaled independently of each other. During busy periods when new shows are released, the ‘Download’ component can be scaled up to handle the increased load, without having to scale up every component, which makes elastic scaling more feasible and reduces costs.

Reusability: Components fulfil a small, specific function. This means that they can more easily be adapted for use in other systems, services or products. The ‘Transcode’ component could be used by other business units, or even turned into a new business, perhaps offering transcoding services for other groups.

At this level of detail, the benefits of a microservice model over a monolithic model seem obvious. So if that’s the case - why is this pattern only recently in vogue? Where has it been all my life?

If this is so great, why hasn’t it been done before?

There are two answers to this question. One is that it has - to the best of our technical capabilities, and the other is that more recent technical advances have allowed us to take it to a new level.

When I started writing the answer to this question, it turned into a long description, so I’m actually going to separate it into another article and publish it a little later2. At this stage, I will skip the journey from single program to many programs, ignore ESBs and Service Orientated Architecture, component design and bounded contexts, and so on.

Those who are interested can read more about the journey separately. Instead I’ll say that in many ways we’ve been doing this for a while, but with the recent explosion in popularity of container technology (Docker in particular) and in orchestration technology (such as Kubernetes, Mesos, Consul and so on) this pattern has become much more viable to implement from a technical standpoint.

So if we take it as a given that we can implement a microservice arrangement, we need to think carefully about the should. We’ve seen the high-level theoretical benefits, but what about the challenges?

What’s the problem with microservices?

If microservices are so great, what’s the big deal? Here are some of the biggest issues I’ve seen.

Increased complexity for developers

Things can get a lot harder for developers. In the case where a developer wants to work on a journey, or feature which might span many services, that developer has to run them all on their machine, or connect to them. This is often more complex than simply running a single program.

This challenge can be partially mitigated with tooling3, but as the number of services which makes up a system increases, the more challenges developers will face when running the system as a whole.

Increased complexity for operators

For teams who don’t develop services, but maintain them, there is an explosion in potential complexity. Instead of perhaps managing a few running services, they are managing dozens, hundreds or thousands of running services. There are more services, more communication paths, and more areas of potential failure.

Increased complexity for devops

Reading the two points above, it may grate that operations and development are treated separately, especially given the popularity of devops as a practice (which I am a big proponent of). Doesn’t devops mitigate this?

The challenge is that many organisations still run with separated development and operations teams - and a organisation that does is much more likely to struggle with adoption of microservices.

For organisations which have adopted devops, it’s still hard. Being both a developer and an operator is already tough (but critical to build good software), but having to also understand the nuances of container orchestration systems, particularly systems which are evolving at a rapid pace, is very hard. Which brings me onto the next point.

It requires serious expertise

When done by experts, the results can be wonderful. But imagine an organisation where perhaps things are not running smoothly with a single monolithic system. What possible reason would there be that things would be any better by increasing the number of systems, which increases the operational complexity?

Yes, with effective automation, monitoring, orchestration and so on, this is all possible. But the challenge is rarely the technology - the challenge is finding people who can use it effectively. These skillsets are currently in very high demand, and may be difficult to find.

Real world systems often have poorly defined boundaries

In all of the examples we used to describe the benefits of microservices, we spoke about independent components. However in many cases components are simply not independent. On paper, certain domains may look bounded, but as you get into the muddy details, you may find that they are more challenging to model than you anticipated.

This is where things can get extremely complex. If your boundaries are actually not well defined, then what happens is that even though theoretically services can be deployed in isolation, you find that due to the inter-dependencies between services, you have to deploy sets of services as a group.

This then means that you need to manage coherent versions of services which are proven and tested when working together, you don’t actually have an independently deployable system, because to deploy a new feature, you need to carefully orchestrate the simultaneous deployment of many services.

The complexities of state are often ignored

In the previous example, I mentioned that a feature deployment may require the simultaneous rollout of many versions of many services in tandem. It is tempting to assume that sensible deployment techniques will mitigate this, for example blue/green deployments (which most service orchestration platforms handle with little effort), or multiple versions of a service being run in parallel, with consuming channels deciding which version to use.

These techniques mitigate a large number of the challenges if the services are stateless. But stateless services are quite frankly, easy to deal with. In fact, if you have stateless services, then I’d be inclined to consider skipping microservices altogether and consider using a serverless model.

In reality, many services require state. An example from our video sharing platform might be the subscription service. A new version of the subscriptions service may store data in the subscriptions database in a different shape. If you are running both services in parallel, you are running the system with two schemas at once. If you do a blue green deployment, and other services depend on data in the new shape, then they must be updated at the same time, and if the subscription service deployment fails and rolls back, they might need to roll back too, with cascading consequences.

Again, it might be tempting to think that with NoSQL databases these issues of schema go away, but they don’t. Databases which don’t enforce schema do not lead to schemaless systems - they just mean that schema tends to be managed at the application level, rather than the database level. The fundamental challenge of understanding the shape of your data, and how it evolves, cannot be eliminated.

The complexitities of communication are often ignored

As you build a large network of services which depend on each other, the liklihood is that there will be a lot of inter-service communication. This leads to a few challenges. Firstly, there are a lot more points at which things can fail. We must expect that network calls will fail, which means when one service calls another, it should expect to have to retry a number of times at the least. Now when a service has to potentially call many services, we end up in a complicated situation.

Imagine a user uploads a video in the video sharing service. We might need to run the upload service, pass data to the transcode service, update subscriptions, update recommendations and so on. All of these calls require a degree of orchestration, if things fail we need to retry.

This retry logic can get hard to manage. Trying to do things synchronously often ends up being untenable, there are too many points of failure. In this case, a more reliable solution is to use asynchronous patterns to handle communication. The challenge here is that asynchronous patterns inherently make a system stateful. As mentioned in the previous point, stateful systems and systems with distributed state are very hard to handle.

When a microservice system uses message queues for intra-service communication, you essentially have a large database (the message queue or broker) glueing the services together. Again, although it might not seem like a challenge at first, schema will come back to bite you. A service at version X might write a message with a certain format, services which depend on this message will also need to be updated when the sending service changes the details of the message it sends.

It is possible to have services which can handle messages in many different formats, but this is hard to manage. Now when deploying new versions of services, you will have times where two different versions of a service may be trying to process messages from the same queue, perhaps even messages sent by different versions of a sending service. This can lead to complicated edge cases. To avoid these edge cases, it may be easier to only allow certain versions of messages to exist, meaning that you need to deploy a set of versions of a set of services as a coherent whole, ensuring messages of older versions are drained appropriately first.

This highlights again that the idea of independent deployments may not hold as expected when you get into the details.

Versioning can be hard

To mitigate the challenges mentioned previously, versioning needs to be very carefully managed. Again, there can be a tendency to assume that following a standard such as semver[4] will solve the problem. It doesn’t. Semver is a sensible convention to use, but you will still have to track the versions of services and APIs which can work together.

This can get very challenging very quickly, and may get to the point where you don’t know which versions of services will actually work properly together.

Managing dependencies in software systems is notoriously hard, whether it is node modules, Java modules, C libraries or whatever. The challenges of conflicts between independent components when consumed by a single entity are very hard to deal with.

These challenges are hard to deal with when the dependencies are static, and can be patched, updated, edited and so on, but if the dependencies are themselves live services, then you may not be able to just update them - you may have to run many versions (with the challenges already described) or bring down the system until it is fixed holistically.

Distributed Transactions

In situations where you need transaction integrity across an operation, microservices can be very painful. Distributed state is hard to deal with, many small units which can fail make orchestrating transactions very hard.

It may be tempting to attempt to avoid the problem by making operations idempotent, offering retry mechanisms and so on, and in many cases this might work. But you may have scenarios where you simply need a transaction to fail or succeed, and never be in an intermediate state. The effort involved in working around this or implementing it in a microservice model may be very high.

Microservices can be monoliths in disguise

Yes, individual services and components may be deployed in isolation, however in most cases you are going to have to be running some kind of orchestration platform, such as Kubernetes. If you are using a managed service, such as Google’s GKE4 or Amazon’s EKS5, then a large amount of the complexity of managing the cluster is handled for you.

However, if you are managing the cluster yourself, you are managing a large, complicated, mission critical system. Although the individual services may have all of the benefits described earlier, you need to very carefully manage your cluster. Deployments of this system can be hard, updates can be hard, failover can be hard and so on.

In many cases the overall benefits are still there, but it is important not to trivialise or underestimate the additional complexity of managing another big, complex system. Managed services may help, but in many cases these services are nascent (Amazon EKS was only announced at the end of 2017 for example).

Networking Nightmares

A more traditional model of services running on known hosts, with known addresses, has a fairly simple networking setup.

However, when using microservices, generally there will be many services distributed across many nodes, which typically means there’s going to be a much more complicated networking arrangement. There will be load balancing between services, DNS may be more heavily used, virtual networking layers, etc etc, to attempt to ‘hide’ the complexity of this networking.

However, as per Tesler’s Law (or the Law of Conservation of Compexlity), this networking complexity is inherent - when you are finding real, runtime issues in larger scale clusters, it can often be at a very low networking level. These sorts of issues can be very hard to diagnose. I have started tracking some examples at the end of the article, but I think that Tinder’s Migration to Kuberenetes shows this challenge very well.

Overall - the transition is still likely to be for the best, but doesn’t come without some serious challenges at the networking level, which will require some serious expertise to deal with!

The Death of Microservice Madness!

Avoid the madness by making careful and considered decisions. To help out on this I’ve noted a few questions you might want to ask yourself, and what the answers might indicate:

You can download a PDF copy here: microservice-questions.pdf

Final Thoughts: Don’t Confuse Microservices with Architecture

I’ve deliberately avoided the ‘a’ word in this article. But my friend Zoltan made a very good point when proofing this article (which he has contributed to).

There is no microservice architecture. Microservices are just another pattern or implementation of components, nothing more, nothing less. Whether they are present in a system or not does not mean that the architecture of the system is solved.

Microservices relate in many ways more to the technical processes around packaging and operations rather than the intrinsic design of the system. Appropriate boundaries for components continues to be one of the most important challenges in engineering systems.

Regardless of the size of your services, whether they are in Docker containers or not, you will always need to think carefully about how to put a system together. There are no right answers, and there are a lot of options.

I hope you found this article interesting! As always, please do comment below if you have any questions or thoughts. You can also follow some lively discussions on:

Appendix: Further Reading

The following links might be of interest:

- Martin Fowler - Bounded Context - Martin’s articles are great, I’d thoroughly recommend this.

- Martin Fowler - Microservices - An often recommended introduction to the pattern.

- Microservices - Good or Bad? - Björn Frantzén’s thoughts on microservices, after reading this article.

- When Not To Do Microservices - Excellent post on the topic from Christian Posta

- Sean Hull - 30 questions to ask a serverless fanboy - Interesting thoughts on the challenges of serverless, from a serverless fan!

- Dave Kerr - Monoliths to Microservices - Practical tips for CI/CD and DevOps in the Microservice world - A recent conference presentation I did on devops with microservices.

- Alexander Yermakov - Microservices without fundamentals - A response to this article, with Alex’s thoughts and counterpoints to the points raised here (see also Microservices as a self sufficient concept)

Please do share anything else you think makes great reading or watching on the topic!

Thanks

Thanks José from campusmvp.es for having the article translated in Spanish - La muerte de la locura de los microservicios en 2018!

Case Studies

Some interesting examples of experiences I am collecting of larger organisations who have made large scale transitions to microservices:

References

-

https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=microservice ↩︎

-

If you don’t want to miss the article, you can subscribe to the RSS Feed, or follow me on LinkedIn or Twitter. ↩︎

-

Docker Compose is a good solution, Fuge is very clever, and there is also the option of running orchestration locally as is the case with something like MiniKube. ↩︎

-

Google Kubernetes Engine, a managed service from Google Cloud Platform for Kubernetes: https://cloud.google.com/kubernetes-engine/ ↩︎

-

Amazon Elastic Container Services for Kubernetes, a managed service from Amazon Web Services for Kubernetes: https://aws.amazon.com/eks/ ↩︎